Agronomy Update

Aug 25, 2025

Farm Stress During Tough Times

The farm economy is really tough right now, and it can be a challenge to remain optimistic in the face of these headwinds. Harvest has been a challenge so far with the uncooperative weather, uneven crop maturity and weed issues. Add on to that the state of commodity markets and it wouldn’t be surprising if you or your loved ones are dealing with symptoms of stress. These can be physical or emotional and it is important not to ignore the signs. Physical symptoms can manifest as achy shoulders and neck, rapid heart rate or stomach problems. A lack of patience and difficulty making decisions may not just be due to a lack of sleep. Stress can slow you down and make it difficult to do what you need to do. While it is a busy time of year, it might be more productive to slow down and take some time with friends and family, or decompress with a hobby, when you’re able.We are blessed to live in a tight knit community and you don’t have to look far to see neighbors supporting neighbors. If you notice these symptoms in a family member, friend or neighbor, don’t be afraid to reach out and show support.

Developing a Kochia Management Strategy

Kochia was the standout weed this year and what has worked in past years did not do the trick this season. Several factors likely contributed to this situation including weather patterns, planting timing, herbicide resistance and crop rotation. This year we are likely battling late emerging kochia which germinated in July or early August, and those plants can still set seed before winter. Understanding kochia biology and being strategic about management decisions and herbicide selection will be critical to get this weed under control. While there is the potential for a significant seed bank going into 2026, the good news is that kochia weed seed is only viable for a few years so being aggressive in the short term could make a big difference in the weed pressure you face long term.

Dr. Charles Geddes with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada has conducted extensive research on kochia management and this work has identified several opportunities to get a leg up. One key finding is the identification of a critical period in August where we have the opportunity to prevent kochia seed production. After durum or wheat harvest, for example, kochia will re-grow and produce seed. In his research, applying glyphosate plus sharpen 10 days post-harvest reduced seed production by up to 75-100% on a population of both glyphosate resistant and susceptible individuals. A pre-harvest application was less effective but still reduced seed production by about half compared to the untreated control. To manage the group 14 resistant individuals, you could add 2,4-D to that tank mix as well. It might not be feasible to spray entire fields post-harvest, but you can use this strategy to manage kochia patches to prevent seed production and subsequent spread. Kochia seed has been found more than a half mile from where the original plant was located.

Plant competition is free weed control, however, kochia is one of our earliest emerging weeds and can get ahead of our spring planted crops. Planting winter wheat in a pulse rotation can reduce kochia populations through competition in the early spring. On top of that, winter wheat harvest occurs before kochia has produced seeds giving you a nice window for fall weed control. Substituting winter wheat for spring wheat reduced kochia density by 74% by the third year of a rotation where winter wheat was present in two out of every four years (Geddes, 2023). Avoid chem fallow where possible, as this leads to proliferation of kochia seed and increases the spread of herbicide resistant weeds.

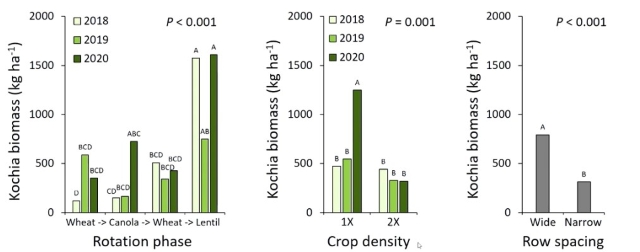

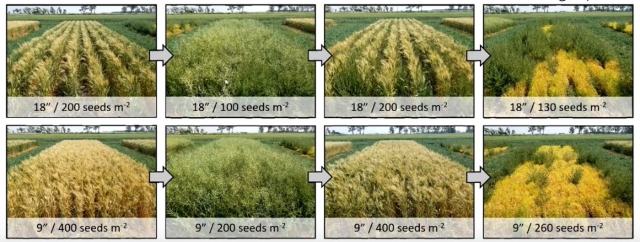

When planning for next season, consider your crop rotation and planting density in fields with high kochia populations. Lentil production is the largest contributor to our kochia population because of the limited control options, so avoid heavily infested fields when planting pulse crops. The chart below shows data from a four-year crop rotation study conducted by Dr. Geddes where he evaluated the effect of crop density (plant population) and row spacing on kochia in a wheat- canola-wheat-lentil rotation.

Data and images above are from the “Contending with Kochia” presentation by Dr. Charles Geddes

Lentil (left graph, far right picture) consistently had the highest kochia biomass by a wide margin. Increased crop density where they doubled the normal seeding rate for each crop, reduced kochia biomass in one out of the three study years. Narrower rows (9 vs 18 inches) reduced kochia biomass by more than half. While most dryland farmers in our region already utilize narrow row spacing, this highlights the importance of establishing a good stand to out-compete kochia. Managing saline areas where crops fail and kochia thrives could will also help reduce the kochia seed bank long term.

Herbicide resistance in kochia is a growing problem. Canadian weed scientists have been surveying kochia populations for many years and the trends are concerning. Between 2012 and 2017, glyphosate resistance in Alberta kochia populations increased from 4% to 54%, and Group 2 resistance is now essentially universal. More recently, resistance to dicamba and fluroxypyr has also been confirmed in these surveys (2017 and 2021), with prevalence on the rise. In North Dakota we have observed similar trends with Group 2 herbicides and glyphosate. Dr. Brian Jenks, NDSU weed scientist, has confirmed the presence of dicamba resistant populations in North Dakota, and genetic testing has proven that group 14 resistance is present in Williams and Divide Counties.

The products we have been using effectively for years no longer give the same level of control. We will have to combine agronomic management with a layered herbicide strategy. Consider incorporating Group 15 (e.g., Zidua, Anthem Flex, Authority Supreme), or Group 5 (e.g., metribuzin) products to diversify the modes of action we are using against kochia. The use of a Group 3 product like Sonalan can provide 40-70% control, but requires incorporation. The use of this product might be another way to manage heavy kochia patches or field edges, and can be applied in the fall ahead of many crops including canola. By incorporating different herbicide modes of action we not only improve control, but can slow the spread of resistant weeds.

Effective kochia management will require a long-term strategy, particularly within annual cropping systems. This can be challenging in the current economic environment with lower commodity prices. In some cases, establishing perennial forages may be a practical solution for fields with persistent kochia pressure. Perennial crops can outcompete kochia over time, help deplete the weed seed bank, and offer additional agronomic benefits such as improved soil fertility and better management of saline soils.

Kochia is a tough and adaptive weed—but with an integrated approach, it can be managed. Focus on:

- Timely herbicide applications during vulnerable growth stages

- Strategic crop rotations and increased plant to plant competition

- Managing herbicide resistance through diverse modes of action

- Long-term solutions like perennials in problem areas

Staying ahead of this weed will take persistence and planning, but the payoff will be fewer headaches—and seeds—in the years to come.

Dr. Audrey Kalil

Agronomist/Outreach Coordinator

Late-Season Soybean Update

Over the past few days, we’ve been out in the field staging soybeans and checking for any issues in this year’s crop. Most of the soybeans we’ve walked through are currently at the R4 to R5 growth stage. For those unfamiliar, R5 begins when the seeds inside the pods on the upper four nodes are at least 1/8 of an inch long. At the same time, it’s not unusual to still see a few flowers forming—soybeans are always pushing to grow, even as the season winds down.August Moisture is Key

August is a critical month for soybeans as the crop shifts focus to pod fill. This stage requires ample moisture, and it's a common mistake to back off on irrigation too early. While it may feel like we’re nearing the end of the season, this is not the time to ease up on water.Late summer often brings drier conditions, and if Mother Nature doesn’t cooperate, it’s up to us to ensure soybeans have what they need to finish strong. Maintaining consistent moisture through pod fill can make a significant difference in final yield. Infrequent, heavy irrigation is better than frequent light irrigation. That allows the crop canopy to dry out and reduces disease development.

Disease Watch: Blight and White Mold

So far, we've observed some bacterial blight in a few fields. While generally not a major concern, it’s something to keep an eye on. However, we’ve also seen advanced symptoms of white mold in a few locations. While levels remain low for now, white mold in this season spells out problems for future crops.If you spot white mold, you're already at the maintenance stage, and you won’t be able to eliminate it this season. Applying a fungicide at this stage will likely not reduce yield loss due to disease.

Why Preventive Fungicide Matters

This is why we strongly recommend applying fungicides before disease symptoms appear. Preventive applications offer multiple benefits:- Protecting yield potential

- Reducing the risk of late-season disease

- Keeping the plant healthier during critical pod-fill stages

At this point in the season, soybeans are especially vulnerable due to high heat, moisture, and dense canopies. All those pods and flowers mean the plants are working hard—and under stress—which makes them more susceptible to disease pressure.

A timely fungicide application keeps the crop healthier and more productive through the end of the growing season. In the long run, it’s an investment that often pays off—and you’ll be glad you took action.

Zach Weiland

Agronomist/Future Location Manager, Fairview

Soil Sampling Reminder

As we head into the fall season, we want to remind all growers— especially those wrapping up wheat harvest—to contact us about soil sampling needs.It’s best to collect soil samples before any tillage work begins. Sampling undisturbed soil gives us a clearer, more accurate picture of the nutrient levels and conditions within the top six inches. This data is essential for making informed decisions about your fields going

forward.

Get in touch with us soon to schedule your sampling while the ground is still idle.

Cutting Corn for Silage

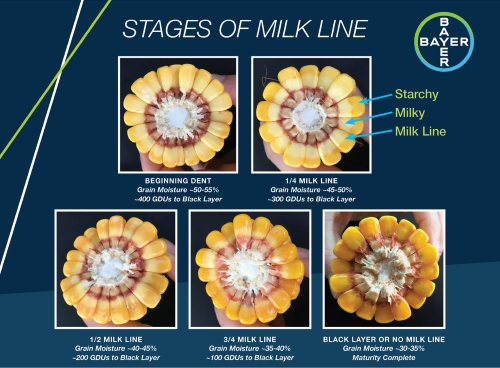

Planning for corn silage harvest should begin when the crop reaches the milk stage. Proper harvest management is essential for producing high-quality silage, and that starts with timing.One of the best tools for determining the right time to harvest silage corn is the kernel milk line. This visible line on the corn kernel separates the milky, liquid starch from the hard, solid starch and gives a good visual estimate of moisture content. To check it, break an ear of corn and observe the milk line’s progression.

Silage harvest typically begins at around 68% total plant moisture, which occurs when kernels reach full dent or early dough stage. The milk line will be halfway to two thirds down from the kernel crown.

Harvesting at this point helps prevent kernels from becoming too dry later in the harvest, which can reduce silage quality.

Keep in mind that corn dry-down rates average 0.5% to 0.6% per day, depending on weather conditions. Once chopping begins, it’s critical to minimize exposure to oxygen by processing and packing silage quickly and efficiently to preserve quality.

Julia Seiller

Agronomist, Fairview Location

Dry Bean Disease Update

Late-season thunderstorms combined with moderate temperatures have created ideal conditions for disease development in dry bean fields. Last week, we identified several different diseases across the region. While there might not be much we can do now, diseases present this season can impact future crops so be sure to correctly identify disease issues.White Mold

White mold is the most common disease that growers battle in dry bean. This fungal disease will likely be common this year with the ab- normally wet and mild conditions. We observed white mold in several fields last week. You can recognize it easily by tissue rotting or bleaching, fluffy white fungal mycelium and black sclerotia.

Without the long history of white mold in this region, the presence of white mold this year may or may not cause noticeable yield loss. The impact on yield depends on the severity of the disease. White mold is usually sporadic through the field initially and thus, on average, you could still obtain acceptable yields. However, the sclerotia can contaminate the grain and will remain in the field for many years so check fields to determine of this disease is present. Avoid moving sclerotia to other fields either though seed or equipment.

Common Bacterial Blight or Bacterial Brown Spot

Bacterial diseases frequently occur after storms that damage plants through high winds, heavy rains and hail. Unlike fungal pathogens, bacteria require wounds to enter plants. These diseases are recognizable by brown lesions surrounded with a yellow halo that become brittle and fall out, leaving holes in the leaves. Yield losses result from reduced photosynthesis as well as reduced seed and seed quality.

Bacterial brown spot. R. Harveson, Univ. of Nebraska

Common bacterial blight. S. Markell, NDSU

Disease can spread via infected seed and crop residue. Early infection leads to greater yield loss, making it essential to reduce the amount of pathogen present in fields planned for future dry bean production. Avoid planting seed from infected fields. Crop rotation is also important—plant dry beans only every third or fourth year to allow infected residue to break down. Corn and small grains are not susceptible and are good rotational options.

Susceptibility to Common Bacterial Blight varies among pinto bean varieties. For example, Torreon and Othello are susceptible, while ND Falcon is considered highly tolerant (2024 NDSU Dry Bean Variety Guide).

Fusarium Yellows/Wilt

Fusarium Yellows (or Wilt) is caused by soil-borne Fusarium fungi that infect the plant's vascular system, leading to premature wilting, empty pods and plant death. You can diagnose this disease by sectioning the stem in affected areas of the field. Instead of being white, the tissue inside the stem will be a dark, reddish brown.

Management options are limited and losses can be severe, so use long crop rotations and sanitation measures to prevent this pathogen from becoming established in your fields. There have been observations that Fusarium wilt is less severe in dry beans following alfalfa cultivation. The disease can be spread to other fields through infected seed, crop residue and contaminated soil. In other crops we manage wilt by planting resistant varieties. While breeding efforts are underway, resistant dry bean varieties are not yet available.

Anthracnose

Anthracnose is caused by the fungal pathogen Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. We observed leaf vein discoloration and pod symptoms consistent with this disease in one dry bean field.

Anthracnose leaf lesions. S. Markell, NDSU.

This pathogen can be spread by seed and crop residue so, as with many of the diseases we discussed, do not reuse seed from affected fields and try not to move the infected crop residue into a healthy field during harvest or through tillage equipment. Wind dispersal of this pathogen is also possible, so planting dry beans next to fields with a history of Anthracnose could increase disease risk.

While the symptoms we observed were not severe, this pathogen can significantly reduce yield and grain quality in humid and cool years. Anthracnose can survive in the soil for two to three years, and up to five. Multiple races of this pathogen can be present in the environment and host resistance is race specific. At the moment, pinto bean varieties grown in our region are susceptible to race 73 which was detected in North Dakota. Foliar fungicides for Anthracnose are typically applied at flowering and while this can reduce losses due to disease related quality issues, it may not provide complete control.

As the growing season progresses, be sure to reach out if you need help with disease diagnosis. Some diseases like white mold have more straight forward solutions, while others like Common bacterial blight, Fusarium wilt and Anthracnose might require more proactive management. Practicing long crop rotations, planting disease-free seed, minimizing the spread of pathogens, and using tolerant varieties when available will help ensure the long-term success of dry bean production in these fields.

For more information, review the NDSU Dry Bean Production Guide

Dr. Audrey Kalil

Agronomist/Outreach Coordinator