Agronomy Update

Sep 05, 2025

On The Horizon Podcast

Farming is rewarding, but it can also be one of the most stressful professions. Unpredictable weather and markets, long hours, family dynamics, and isolation all take their toll. In this episode, we sat down with rural mental health specialist Monica McConkey of Eye On the Horizon Consulting to talk about the realities of farm stress, recognizing the signs, starting tough conversations, and building healthier coping strategies. Monica shared powerful insights for farmers, spouses, and ag industry professionals on how to support one another during these challenging times. We also discussed suicide prevention, compassion fatigue, and the importance of strong relationships both at home and in the workplace.

Resources mentioned in this episode:

- Farm State of Mind (national resources, searchable by state):https://farmstateofmind.org

- North Dakota: Together Counseling – Farm to Farm Therapy (grant - supported services): https://togethercounseling.org

- Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (available 24/7): Dial or text 988

- Contact Monica directly: 218-280-7785 monicamariekm@yahoo.com

Listen to the episode on YouTube, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

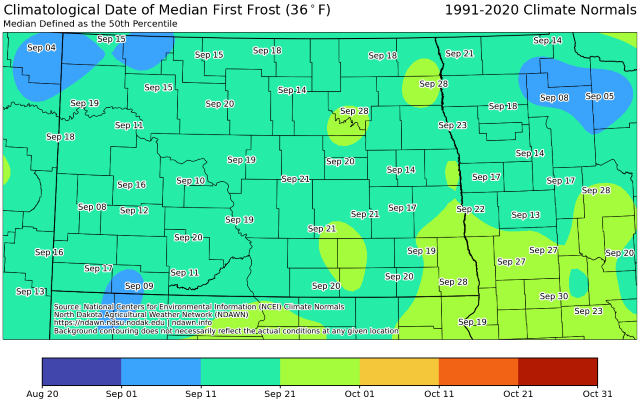

Powdery Mildew in Canola and Field Pea

Powdery mildew is a fungal disease that can occur on several crops but the pathogen is host specific. In canola powdery mildew is caused by Erysiphe cruciferum and as the name implies this pathogen infects Brassica species (crucifers). In peas, the disease is caused by Erysiphe pisi, while in wheat, it is caused by Blumeria graminis f. sp. tritici. Moderate temperatures combined with high relative humidity and morning dew have created ideal conditions for the development of powdery mildew. While relatively uncommon in our area, powdery mildew is causing significant harvest challenges this year in canola, and symptoms have also been observed in pea fields.Canola

There is limited information on powdery mildew in canola, likely because it typically infects late in the season and yield impact is minimal. The fungal spores are dispersed by wind and infect host plants, even without the presence of water. The disease begins as white, powdery spots on the plant, which eventually coalesce and cover large areas. These spots consist of fungal spores and mycelium, which can further spread the infection to neighboring plants.

Powdery mildew on canola. Photo: S. Marcroft

There are few management options for powdery mildew in canola beyond crop rotation. However, because the pathogen is wind- dispersed and canola is widely grown, rotation may offer limited control. No fungicides are currently registered for powdery mildew control in canola, and resistant varieties are not available.

While yield loss might not be a major concern, the disease poses a significant challenge during harvest. When fungal spores and mycelium become wet, they form a sticky mass that is difficult to clean and can accumulate on harvesting equipment. This buildup may even become a fire hazard due to overheating machinery. Power washing with detergent has proven to be the most effective method for removing the fungal mat from combines.

Powdery mildew coating equipment. Photo: Christine Bennink

It would be great to have an easy solution to this headache but it doesn't seem that this is the case. On the bright side it appears that there is a great canola crop out there this year so I guess this frustrating problem comes with a silver lining.

Field Pea

Powdery mildew is an economically important disease in field pea across many growing regions, although it is less commonly observed in our area. The symptoms are visually similar to those seen in canola, so it's understandable that they could be mistaken for the same pathogen.

Powdery mildew symptoms. Photo: S. Markell, NDSU

There are foliar fungicides available which are highly effective against powdery mildew and can reduce yield loss due to this disease. Application timing is normally around early pod fill, so slightly later than we would apply a fungicide for Ascochyta blight. This year it seems that infection may have occurred later on in the growing season and so hopefully not much yield loss occurred.

The best way to manage powdery mildew in pea is to grow a resistant variety. Resistance in this case is strong and durable. You will not need to apply a fungicide for powdery mildew if you grow a resistant variety. Use the Saskatchewan Grain Crop Variety Guide to find CDC and AAC resistant varieties. NDSU variety guides intermittently provide that information for other varieties so consult with your seed dealer. Many options are available for both green and yellow peas. With so many variables to manage in pulse crop production, choose a resistant variety so there is one less thing on your plate.

Dr. Audrey Kalil

Agronomist & Outreach Coordinator

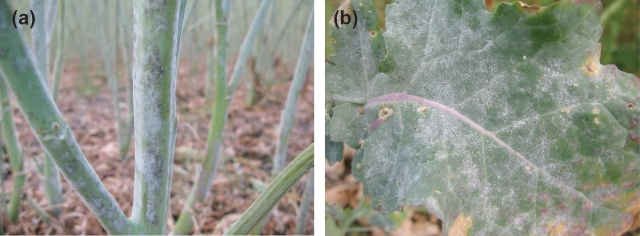

Wheat Stem Sawfly: Harvest Clues and Management Planning for Next Season

Harvest season often reveals what’s been quietly at work all summer. If you noticed patches of lodged wheat, stems that snapped off just above the ground, or stubble filled with sawdust-like frass, there’s a good chance wheat stem sawfly was the culprit. This pest has long been a challenge in western North Dakota and eastern Montana, affecting both hard red spring wheat and durum. In heavily infested fields, losses of up to 80% have been recorded from lodged plants.Identifying Wheat Stem Sawfly

The adult sawfly is a small, dark wasp-like insect with yellow abdominal markings, emerging in late June and early July. Females lay eggs inside elongating wheat stems, where larvae feed unseen. As plants mature, larvae chew a notch near the stem base, plug the stem with frass, and overwinter as mature larvae in a protected stub.

Telltale signs include:

Lodged stems cut cleanly near the soil line

Sawdust-like frass inside stems

S-shaped larvae curled in the lower stem when split open

If these symptoms were present during harvest, now is the time to plan your 2026 management strategy.

Figure from Peirce et al 2022. (A) Adult wheat stem sawfly, (B) End of season cut plants, (C) wheat stem sawfly eggs in a stem (D) Bracon cephi parasitoid larva consuming wheat stem sawfly larva in the stem, and (E) A highly infested field with significant lodging damage. Photos: K. Dawson (A), E. Peirce (B, C), and D. Cockrell (E).

Key Management Strategies

1. Solid-Stemmed Wheat

Solid-stemmed cultivars are one of the most reliable defenses, reducing larval survival and limiting lodging losses. Modern solid- stemmed varieties yield comparably to hollow-stemmed types under pressure and don’t hinder natural parasitoid activity.

Examples of popular solid stemmed varieties:

Spring Wheat

SY Longmire

Dagmar

Winter Wheat

Bobcat

Durum

2. Crop Rotation

Rotating to non-host crops (pulses, safflower, sunflower, flax, corn, etc.) can break sawfly cycles in a specific field, although reinfestation from nearby grass borders and especially infested wheat fields from the year before is possible. Barley and triticale can also host the pest so these will not be effective rotation options. Oats, however, canserve as a trap crop. The wheat stem sawfly can lay their eggs in oats but the larvae do not survive to maturity.

3. Harvest Timing & Equipment Choices

Swathing or using a stripper header is critical in heavily infested fields (>15% of stems showing sawfly activity). Swathing early, when kernel moisture drops below 40%, prevents stems from breaking and limits harvest loss. Stripper headers can also salvage grain while conserving parasitoids. Also to be noted, it seems field borders (especially those that border an infected field last year) lodge the worst so swathing outside borders could be warranted as a management practice.4. Chemical Control: Not Recommended

Insecticides are ineffective because sawfly life stages are protected inside stems. Spraying for adults offers little benefit because their emergence is so spread out and sporadic, not to mention insecticides can harm beneficial insects like the Braconid wasps that parasitize on the wheat stem sawfly.Putting It All Together

Wheat stem sawfly thrives in our major wheat systems, making an integrated approach essential. The best investment for next season is selecting a solid-stemmed wheat variety for heavily infested fields, combined with timely harvest management and thoughtful rotation. Monitoring this fall and next summer will help guide future planting decisions.Kyle Okke, CCA

Agile Agronomy LLC & Agronomists Happy Hour Podcast

Alternative Pulse Crops Options

Exploring alternative specialty crops can be a way to hedge against challenging commodity markets. Fortunately, in northwest North Dakota and northeast Montana, we’re well-positioned with access to buyers interested in these niche markets. Adopting a new crop can be intimidating, but thanks to research conducted both locally and across the border, we have a wealth of resources available to guide best practices.Thanks to biological nitrogen fixation, growing legume crops becomes especially advantageous when nitrogen fertilizer prices are high. However, low prices and root rot disease can limit the viability of the common legumes we produce and restricts their frequency in crop rotations. Below are two alternative pulse crops worth considering for our region, along with resources where you can learn more.

Chickpeas

Chickpeas perform well in our typically hot and dry climate, making them a strong option for dryland farmers. Although this year brought challenges—cool, wet conditions in July and August—chickpeas generally tolerate drought as well or better than peas or lentils.

One big selling point is that chickpeas are resistant to Aphanomyces root rot, which can devastate peas and lentils. If you are looking to stretch out your pea and lentil rotation due to root rot, but still want a legume to reduce fertilizer costs then this is the best bet for dryland production. Chickpeas are very susceptible to soil-borne Pythium seed rot, however, so a fungicide seed treatment is essential. While the rhizobia that nodulate chickpeas differ from those for peas and lentils, there are inoculants available that work across all three crops.

While you can grow chickpeas under irrigation, Ascochyta blight becomes a major concern. This fungal disease can infect leaves, pods and stems and is one of the top production constraints of this crop. Even under dryland conditions, a minimum of one fungicide application is typically necessary. It is spread by rainfall, so under irrigation you are probably looking at several fungicide applications. Montana is the top producer of chickpeas, and some farmers intercrop with flax as a way to reduce Ascochyta blight. Popular varieties like ND Crown, CDC Frontier, CDC Orion, and the new variety from Montana State University, MT Bridger, are more resistant to Ascochyta blight compared to Sierra and Sawyer which are extremely susceptible. Even so, anticipate at least one fungicide application and even up to four in a year like this one.

The herbicide program for chickpea is similar to field peas, with the exception that Tough® (Group 6, pyridate) can be used post-emergence for broadleaf control. At higher the rates that can be used in chickpea, it can help manage kochia escapes from fall or pre-plant applications. Chickpeas are indeterminate and will continue growing with any available moisture, so pre-harvest desiccation may be required.

Markets for chickpeas can be volatile, and with higher production costs compared to peas or lentils (due to seed and fungicide expenses), new growers should consider forward contracting to manage risk.

Chickpea production resources:

Growing Chickpea in North Dakota

Growing Chickpea in the Northern Great Plains

Management of Ascochyta Blight in Chickpea

Chickpea Disease Diagnostic Series

Chickpea Weed Management with Dr. Drew Lyon

Post-harvest in Chickpeas with Phil Hinrichs

Chickpea Field Management (Saskatchewan Pulse Growers)

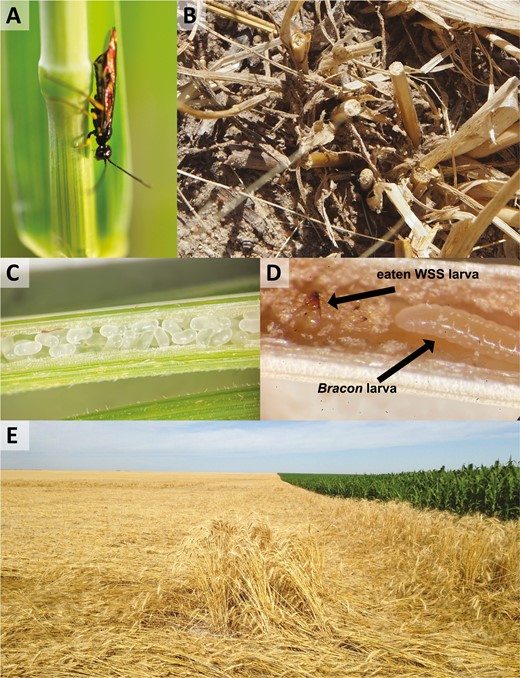

Faba Beans

Faba bean (also known as broad bean) is a staple food in Asia, Africa and Mediterranean nations and is also used for animal feed. Currently grown on limited acres in North Dakota, it is successfully produced in Alberta and under irrigation in Saskatchewan. This crop is going to need more water than our dryland farms typically receive and so should be produced under irrigation in our region.

Faba beans offer several benefits: they tolerate frost (similar to peas), resist Aphanomyces root rot, and are strong nitrogen fixers. While peas and lentils fix about 50% of their nitrogen needs, and dry beans fix roughly 40%, faba beans can fix up to 90%. They nodulate with the same rhizobium species (Rhizobium leguminosarum) as peas and lentils, so inoculant products like LaFix Peat Pea & Lentil can be used.

Non-irrigated trials conducted at the NDSU Langdon REC yielded anywhere from 37 to 94 bu./ac depending on the variety grown and study year. They were planted mid May and harvested mid September in 2021 but harvest timing varied by year. In 2023 the variety trial was harvested October 19th. In general, faba beans require a growing season of 110 to 130 days.

While herbicide choices may be limited, there are pre-emergence products like Spartan Charge that may be used and in crop grass (Select/Assure II) and broadleaf (Varisto) weed control options. Dr. Brian Jenks has done some research on which products are suitable for faba bean (link below). Another challenge is their large seed size and irregular shape which can present difficulties during planting. Greg Stamp from Stamp Seeds discusses strategies to mitigate seeding problems on the latest episode of the Growing Pulse Crops podcast.

“Snowbird” faba bean seed

Of the ~35,000 acres of faba beans grown in Canada, the zero-tannin variety Snowbird dominates and is well-suited for feed and export markets. However, it contains vicine, which can cause favism in susceptible individuals, making it less desirable for food markets. The industry is gradually shifting toward low-vicine, low-tannin varieties, with 37% of insured acres in Canada planted to these types in 2024. Fabelle is one such variety, suitable for human consumption and food ingredients, and outyields Snowbird by 6–13%.

Faba beans grow tall (3–5 feet) and stand well, which simplifies combining. However, like other pulses, they can shatter if left to mature too long, so pre-harvest desiccation is often advisable. Gramoxone is labeled for this use (as "broad bean").

Faba bean production resources:

Faba Bean Tolerance to Pre and Post Herbicides

NDSU Statewide Faba Bean Variety Trials

Faba Bean Micro-Summit 2025

Faba Bean Agronomy

Chocolate spot of Faba Bean

Dr. Audrey Kalil

Agronomist & Outreach Coordinator

Weather and Climate Update