Agronomy Update

May 26, 2025

Perennial Weed Control—Playing the Long Game

While both winter annuals and spring-germinated annual weeds can pose significant challenges in our crops, established perennial weeds are by far the hardest to control, especially once they are established with extensive root systems.

Perennial weeds survive through their root systems, which can be massive. Canada thistle plants can root to depths of six feet with only about 10% of the roots in the top foot of soil. Bindweed plants don’t root quite as deep but can extend 10 to 15 feet beyond the plant once established. Quackgrass too has a sprawling root system where if you pull it in one spot, it can remerge from the ground from several feet away.

That is how these weeds survive our harsh winters and is how they keep popping out of the ground every year if you let them survive. It makes weed control somewhat challenging, and you need products that will translocate all the way through the root system. With summer fallow, we used what was called the “Hunter method” by working the summer fallow until the end of July, then we let the weeds grow until we were closer to a frost around the middle of September. Once the days were getting shorter and the nights were getting colder, we would spray a quart or more of Roundup per acre. At this time of year, the plants were done trying to make seeds and were redirecting all their energy down into the root systems for winter survival, taking the herbicide with it. That is why this worked so well. Today, we depend more on products that will translocate earlier in the year and get the products into the root systems.

Clopyralid is probably the most effective herbicide for Canada thistle control in-crop and has been sold for many years in products like Curtail, Widematch and Stinger. Canada thistle has become a major problem in peas and lentils because there are really no options for perennial weed control in these crops. Once these weeds get started in the pulse acres, they may have established root systems the next year in cereals. This is your opportunity to control them and if you don’t the problem will just get worse. One plant can spread 3 to 6 feet in one to two years.

Two years of Canada thistle root growth. Merrill Ross, Purdue University

That is why tight rotations with pulse crops compound perennial weed issues. When people tell us they need to “keep their options open for pulse crops” the next year, they end up spraying products that will only burn the part of the plant above the ground and won’t touch the roots whatsoever. I have seen growers that actually quit growing pulse crops just because of the weed problems created by not controlling perennial weeds.

Once you have established Canada thistle, it will not be a quick fix, and you will not be able to get control of these weeds in one season. We have seen growers fight Canada thistle for several years before getting it under control, then losing all of the ground they gained with one season of a pulse crop. It will take a combination of using products like clopyralid along with late season spraying of glyphosate for multiple years. Timing with both products is important, because if you spray clopyralid too early on smaller weeds, you are taking the chance of more rhizomes coming up out of the ground after you spray. With the late fall glyphosate, you can be too early, and the glyphosate will not get into the deep roots. Spray too late and plants can be damaged by a severe frost which will limit the uptake of the chemical.

Bindweed is one of the worst weed problems you can have since it will not only hammer your yield but also becomes a huge harvest problem. You can try to burn the leaves and vines down when you desiccate at harvest, but this strategy is hit or miss. You have about a 50/50 chance of hitting and burning bindweed down enough to combine it.

There are no silver bullets for bindweed unless you want to use Tordon as a post-harvest application but then you will not be able to raise any broadleaf crop for several years. One of the better options I have seen is an old Monsanto product called Landmaster BW which is a combination of Round Up plus 2,4-D Amine. The BW in the name was named for bindweed control. The best time to use this is right af- ter harvest when the vines and leaves are still green and actively growing. You have a small window for using this product, but it is kind of like the old Hunter method for killing Canada Thistle with Roundup. The timing has to be right and maybe even the right moon phase, but with perennial weeds, sometimes you just need to be lucky too.

Perennial weeds are a huge problem and are really tough in certain crops. I was once told that one of these products was not a good fit in a lentil rotation, and my reply was “neither is Canada thistle.” Take care of perennial weeds when you can. If you need help figuring out what to use, when to apply it, and how to rotate crops effectively, reach out to our agronomists. That is our specialty and we have tools like FarmQA to help you track perennial weed issues across seasons. Anyone can sell a jug of chemical for a price without knowing anything about it. Our people know the how’s, why’s and when’s so you can conquer perennial weeds, manage chemical resistance and establish a good rotation.

John Salvevold, CCA

Agronomy Division Manager

Using FarmQA for Spray Records

FarmQA is an app and web based tool that can be used for crop scouting, record keeping and farm planning. We offer the use of our account to all of our customers and you can view your fields, scouting reports and recommendations at no cost. To become a user there is a small annual fee, and this will allow you to enter plant dates and spray records either using the app or the web based platform. Spray records are kept across seasons in your account and can be exported as an Excel file. This program makes tracking herbicide applications and planning crop rotations around rotation restrictions much easier.

The home screen of the app is below. To enter a spray record you start by selecting the “advice” tab.

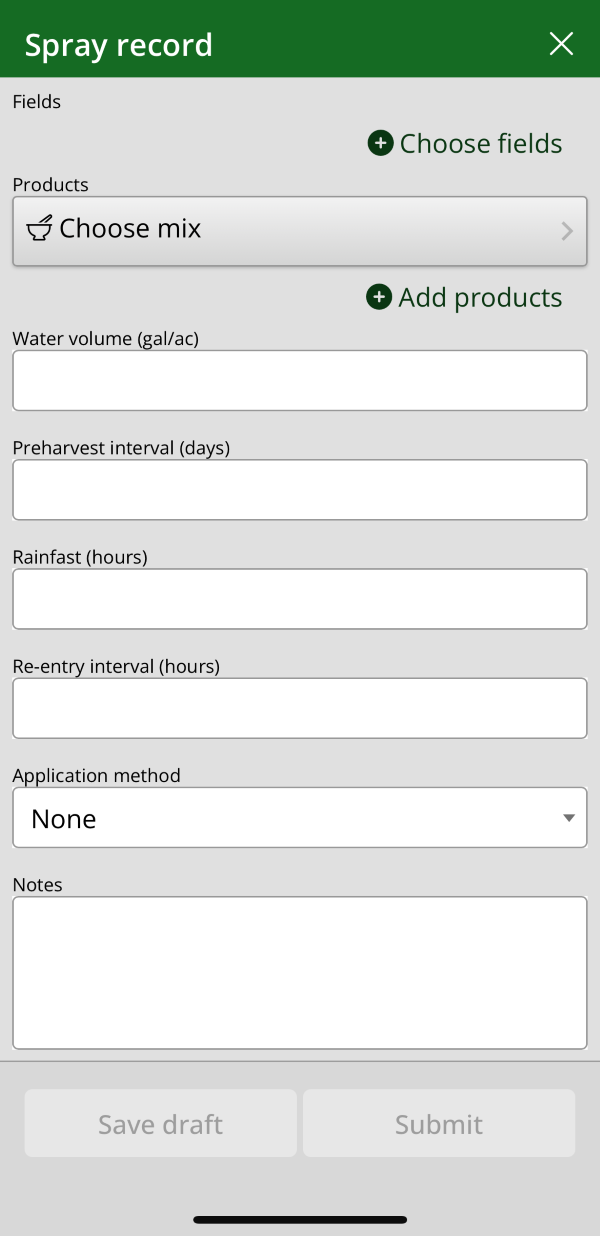

This will take you to either the “recommendations” or “spray records” tab. Click “spray records” and then tap the green plus arrow to add a new spray record. It will make you select a field and then take you to the record keeping screen.

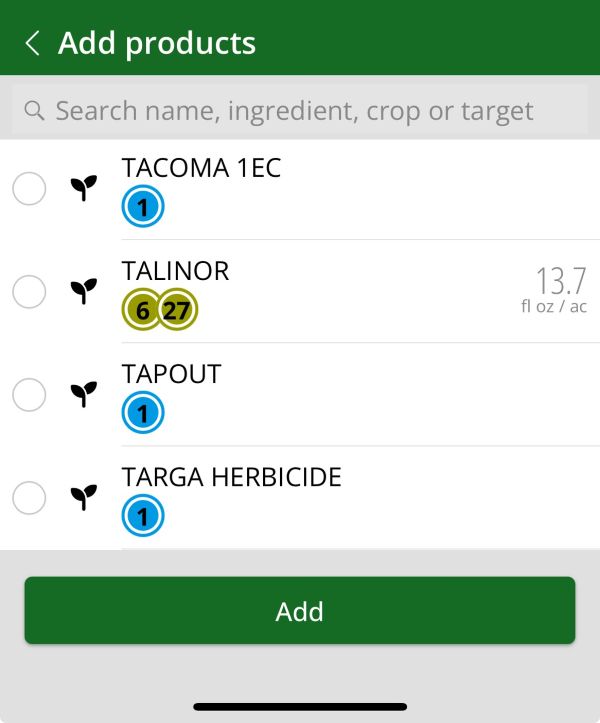

Click the “Add products” button and you can select from all of the products that have been entered into the database (picture below). Make sure to enter the correct application rate, as that might have implications for rotation intervals. Rainfast and re-entry intervals will many times auto-populate based on the product information. Below the product name you can see that the herbicide group is also indicated, which is really helpful when you’re trying to manage herbicide resistant weed populations.

After adding all the information, click “submit.” The spray record will be saved with the date of submission. If you plan to spray multiple fields with the same mix but it will be across multiple days, you can simply select all of those fields, create and submit the report and then use the web-based platform to edit the dates later. All spray records can be edited and exported using the website version of the program.

Perennial and herbicide-resistant weeds require a multi-year management approach. One key advantage of using FarmQA to track pesticide applications—rather than relying on written records—is the ability to automatically export all your application data for every field into a single Excel spreadsheet. As you add the application information over multiple years, this allows you to analyze your long- term herbicide usage trends by group and identify opportunities to diversify your program, helping to prevent resistant and perennial weeds from becoming a serious issue.

If you have any questions about using the FarmQA platform, feel free to contact our agronomy team. To set up a user account, please reach out to Agronomist Sara Erickson at our Williston Agronomy location.

Assessing Nutrient Loss Risk After Recent Rains

While the recent rain has been a welcome change and may finally get us out of drought conditions, it also raises important questions about nutrient management. With fieldwork on hold due to wet conditions, what’s happening to fertilizer applied on the soil surface?

Nitrogen fertilizer applied as urea can undergo different changes depending on environmental conditions. The urea initially reacts with water and an enzyme called urease, which is found in the soil, to convert to ammonium (NH4+). Ammonium is positively charged and so binds to negatively charged soil particles, preventing leaching.

Once converted to ammonium, nitrogen can volatilize and escape as ammonia gas. Thankfully, the recent rain has helped incorporate urea into the soil, reducing the risk of loss via this route.

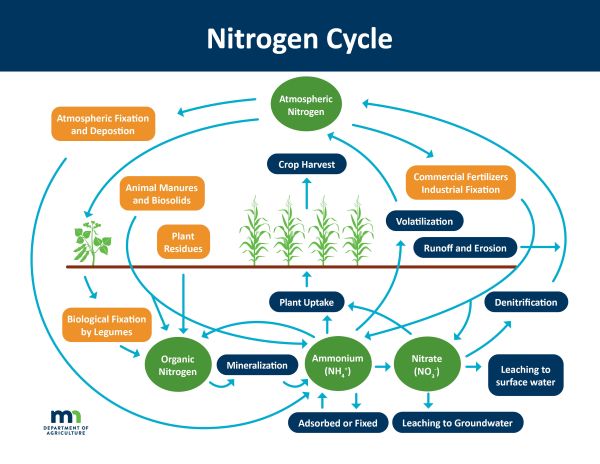

If not lost through volatization, ammonium continues through the nitrogen cycle and transforms into nitrate (NO3+) via nitrification. Nitrate is more soluble and readily taken up by plants but is also more prone to leaching—especially in wet conditions and sandy (coarse) soils. When soils are overly saturated and oxygen levels drop, bacteria that need oxygen start using nitrate instead and convert it to nitrogen gas that can be lost to the atmosphere. The nitrogen cycle below summarizes the various pathways of nitrogen loss. Aside from nitrogen, other nutrients such as sulfur, chloride and potassium can also leach or become unavailable in wet conditions.

The cold weather this past week has also played a role in nutrient availability. Cooler temperatures slow the nitrification process and therefore keeps nitrogen in the ammonium form for longer. In contrast, the supply of nitrogen and phosphorous from mineralization is reduced as decomposition of crop residues by bacteria is a slowed. Cooler temperatures therefore may, or may not, lead to maintaining sufficient nitrogen in the soil for when the temperatures warm back up and the plants need it. Cool and wet conditions tend to limit the availability of phosphorus and potassium.

Nutrient losses aren’t uniform across a field. Areas where water tends to flow or pool are more vulnerable to loss. This key can be used to visually diagnose nutrient deficiencies in wheat and there are excellent pictures available from Montana State University. To confirm nutrient deficiencies, it’s essential to tissue test both symptomatic and healthy plants. Comparing the two side by side will reveal any nutrient gaps.

Pairing tissue tests with corresponding soil samples provides a more complete picture of nutrient availability.

Nutrient deficiencies which are due to cold temperatures alone, like with phosphorous, should resolve once the weather warms and it becomes more available. However, it is possible that tillering in spring wheat or durum could be reduced. Depending on what nutrient deficiency you are dealing with, we have options for top dressing nitrogen and sulfur, and there are foliar products for micronutrients. Regardless of the environmental conditions, applied nitrogen is never 100% efficient. It is always processing through the nitrogen cycle whether conditions are hot and dry or cool and wet. So even if we have to deal with some nutrient losses, we can’t make it rain for our dryland acres and it is certainly better to have a problem we can solve than one we can’t.

Lucas Holmes, M.S. Agronomist, Zahl Location

Make Liberty Work for You: Simple Tips to Boost Herbicide Performance

If you've ever had mixed results with Liberty herbicide (Glufosinate), you're not alone. Some years it performs great—others, not so much. Let’s break down how this tool works and how you can make it work better in your fields.How Liberty Works

Liberty (a Group 10 herbicide) is non-selective, targeting both broadleaves and grasses. It disrupts photosynthesis by stopping the production of glutamine—an essential building block for plant growth. This disruption causes a toxic buildup of ammonia in the plant, leading to cellular death.But here’s the kicker: Liberty needs sunlight and heat to do its job. If you’re spraying in cool, cloudy, or dry conditions, the results will likely be disappointing. On the flip side, when conditions are right, Liberty goes to work fast—symptoms can show up in just a few days.

Keys to Success with Libert

- Spray on Sunny, Warm Days

- Use Enough Water

- Don’t Skip the AMS

- Watch the Humidity

Bottom Line

To get the most out of Liberty, aim for:- Sunlight

- Heat

- Humidity

- High water volumes

- AMS in the tank

Avoid spraying in cool, cloudy, or dry conditions unless you’re okay with slow or spotty results.

Final Recommendation

For best results, use the full labeled rate of Liberty—especially on tough-to-kill weeds like kochia. You need every bit of active ingredient working for you. Pair that with a water conditioner like Class Act NG. It not only supplies the AMS needed to enhance Liberty's activity but al- so includes a surfactant to reduce spray droplet surface tension. That helps droplets stick and spread on hard-to-wet, hairy leaves like ko- chia. Plus, the surfactant acts as a humectant, slowing evaporation on the leaf surface—basically creating artificial humidity—which is key for active uptake and herbicide performance. Use the right rate, the right conditions, and the right tank mix—and let Liberty do its job.Kyle Okke, CCA

Agile Agronomy LLC & Agronomists Happy Hour

Disease Risk in Cool, Wet Soils

Air and soil temperatures took a plunge as the rains moved in, creating the perfect conditions for the seed rot and seedling blight pathogen— Pythium. This pathogen can infect all of our crops, and while the pulses and soybean are most susceptible, wheat and durum are by no means immune (picture below). This pathogen attacks the seed or the germinating seedling resulting in poor stands, stunting and yellowing. Seed treatment with the active ingredients metalaxyl, mefenoxam, ethaboxam or picarbutrazox is highly effective at preventing this disease, but there are no control options in crop.

Pythium symptoms in a Montana wheat field. (Dr. Mary Burrows)

Spring moisture always creates risk of root rot in peas and lentils, as the worst root rot pathogen we deal with—Aphanomyces euteiches— produces swimming spores in saturated soils. Aphanomyces euteiches is native to our soils, so it isn’t a question of IF you have this pathogen in your fields, its just how much and if the numbers are high enough to cause noticeable disease. Wet conditions tends to blow up Aphanomyces populations and can result in high levels of disease if the crop is infected at early growth stages.

Aphanomyces root rot in pea

Cool soil temperatures inhibit the growth of Aphanomyces, so my hope is that the cold weather suppressed spore germination and thus prevented disease development. Watch pea and lentil fields closely over the coming weeks for symptoms. You may need to dig up plants and examine the roots, as low levels of disease may not result in noticeable above ground symptoms. Even though there is nothing that can be done now, fields with root rot should not be planted to pea or lentil again for a minimum of five years (six year rotation) to reduce pathogen populations and risk of future root rot issues. This pathogen can survive in the soil for 10 years or longer, so a short rotation in fields with root rot issues will mean long term problems with growing pulses.

Dr. Audrey Kalil

Agronomist/Outreach Coordinator